Renowned international affairs scholar C Raja Mohan writes in Foreign Policy magazine’s Spring 2023 edition: “The West has an interest in a stronger India that can counter growing Chinese and Russian influence… Washington’s recent offer of a range of technologies to India—including jet engines—underlines the Biden administration’s desire to strengthen ties with New Delhi despite Indian ambivalence on Russia’s war in Ukraine.”

The lines quoted are a fair sample of the main theme and tenor of Mohan’s article: Despite the Indian decision to not parrot the Western line on Ukraine, a magnanimous United States has offered the wayward country arms. This reflects the importance America places upon India as a hedge against the Chinese and the Russians.

Many problems are apparent at once. India has not been ambivalent on the Ukraine war. Having called upon both the warring states to hammer out a peaceful solution, India has made it clear that it will not cut ties with Russia, an old ally. No country would do otherwise.

Coming to the claim that Washington is offering a range of technologies, it is, to say the least, facetious to suggest that any technology is truly on offer. The jet engine in question is the General Electric F414, intended for the Tejas, for which a joint-manufacturing deal is on the table. Transfer of technology for the engine has not been approved by the United States. Scarce resources will be diverted from the Indian Kaveri engine program and from lean, competitive aerospace startups springing up in India for this deal. General Electric has, to date, promised no technology. The assembly of American-made parts is all that India stands to gain. For this raw deal, India is depriving its own nascent aerospace engineering industry of crucial funds.

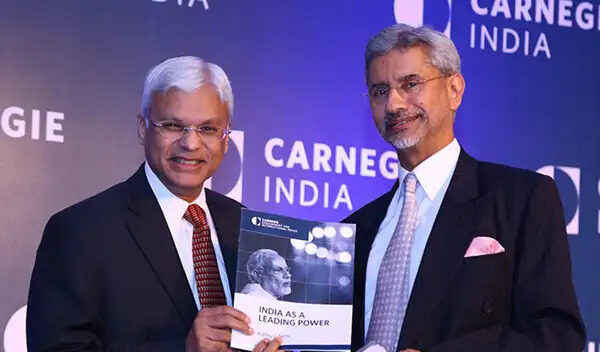

Mohan’s piece is unnerving, even its title: “It’s Time to Tie India to the West.” It goes on to paint a picture of world affairs in which becoming a Western bulwark in Asia is India’s only way forward. The reader is inevitably forced to remind herself from time to time that it is written by an Indian. The lip-smacking is nearly audible as one imagines the writer’s excitement at the prospect of the United States moving in for the kill and co-opting India entirely in this fraught international situation. Mohan, who set up the Delhi outpost of the American Carnegie Endowment, belongs to the influential clique of Indian think-tankers who have expended their considerable energies in priming the Indian state for just such co-optation.

Raja Mohan goes on to contend that India cannot carve out a diplomatic and commercial zone in the Global South the way the Chinese have done without playing second-fiddle to the West, and finds it “difficult to see India [having] much more than a small impact acting alone.” This view conveniently ignores the success of newly-Independent India’s outreach to the postcolonial nations of Asia and Africa while India itself was economically and spiritually emaciated. India’s engagement with the Third World, now sanitised as the Global South, was powerful enough to unnerve the West and China and lead the former to court and isolate in turns what was otherwise a nation in shambles, ruined by colonisation and Partition. The consideration India received was due to fear about India’s ability to lead this part of the world against any nation that should displease it, though India never threatened to do so. It is difficult to understate the importance of this posture, but in Mohan’s version of world affairs it is swept entirely under the carpet. Raja Mohan’s view equally refuses to consider what India could achieve with a similar policy of cooperation with developing nations today, when it can bring to bear considerable economic and military hard power that it lacked in Nehru’s time.

It might appear impossible to convince a nation possessed of all the elements of great power to foreswear an independent role in the world, but therein lies the greatest success of India’s pro-West policy doves. Raja Mohan and likeminded public intellectuals, who wield considerable influence over Indian policy, seem sincerely to suggest that Western assistance, rather than Indian power, coldly and independently pursued, will elevate India to great power status. To Mohan and his fellows in Delhi’s bustling think tank scene, such tying of India to the West is a foregone conclusion, a “gradual but inexorable alignment with the West,” to quote the man. To them, and to a generation of Indian scholars steeped in their deterministic worldview, forward is Westward.

Taken together, the language and content of the essay reflect a deeply entrenched and embarrassingly unambitious view of India’s role in the world. If anything, the brazen demands made in Raja Mohan’s piece for the United States and the collective West to dictate India’s foreign policy– “Drawing New Delhi away from Moscow and enabling it to compete with Beijing have long been U.S. objectives. This should be a goal for the G-7 as well”– is indicative of a mature and emboldened intellectual movement that has grown slowly to become the mainstream of Indian discourse. In the past, American foreign policy objectives, such as stopping India’s nuclear weapons program, were deftly and painstakingly planted as desirable goals in the minds of the Indian establishment by formidable Washington intellectuals like Strobe Talbott and Ashley Tellis before they could be achieved. This approach led to stunning American breakthroughs like the self-sabotaging 2008 Nuclear Deal, presented as the foundation for energy independence by the UPA, and the recent spate of one-sided defence agreements COMCASA, LEMOA & BECA, which do not benefit India in the slightest.

Now, perhaps seeing that the public discourse is free of any clear-headed nationalist voices which recognise this intellectual establishment to be so many Manchurian candidates peddling American influence, and so oppose it, the proverbial gloves have come off and the double-speak of the past has been dispensed with. It is no longer necessary to present the surrender of Indian strategic autonomy, a long-standing American foreign policy objective, as prerequisite for India to become a ‘Responsible Great Power,’ a shockingly condescending phrase that has for decades enthralled Indian politicians and scholars, who have preened every time an American official has uttered it.

The domestic intellectual scene, plied over decades with rhetoric that has maliciously confused the Indian interest with the Western, is now receptive to outright demands for the capture and straitjacketing of India. In this effort, Raja Mohan considers India’s entry into the largely irrelevant G7 “the logical next step for the West.”

Though India stands to benefit enormously from cooperation with Western powers, as it has done in the past, it is treacherous to suggest that India is, or should attempt to be, a Western or Western-aligned power. It is equally outlandish to suggest, as Raja Mohan does, that India must become part of a collective of democratic countries which will cooperate on security. Naively suggesting that internal democracy— which India shares with the powers of Western Europe and North America— invests these nations with common foreign policy objectives, Raja Mohan conceives of a D-10 (A Democracy-10, consisting of the G7 and India, Australia and Japan.) Such fanciful imaginary groupings proliferate in the Indian press, and all of them make the mistake of believing that being democratic in internal functioning automatically gives disparate nations some common interest in international relations. A long line of dictators enthroned or propped up by force across the world by democratic powers, often in place of

democratically elected leaders, gives lie to this idea. It is harmful for a growing power like India to give in to such high-flown notions of democratic cooperation, which have no basis in history, and additionally to spurn key allies on grounds of autocracy. The self-destructive potential of India’s muddleheadedness in this regard has already been borne out in India’s engagement with Myanmar and Iran, where India has forfeited vital diplomatic heft in China’s favour by reducing its engagement with their respective governments to appease Western opinion.

Instead of working on the glaringly obvious principle that a nation’s foreign policy is determined by its national interest, and that alone, outmoded Indian commentators and the policy establishment, paralysed by years of passive and reactive foreign policy, still instinctively seek safety not in Indian strength but in the American alliance system, which has historically been unreliable. Aware of this unreliability, America’s historical allies like Japan and Germany have for the past two decades worked to shore up strategic options to contend with a period of more even-keeled great power competition. At this critical point in the concert of emerging powers in Asia and the world, India cannot be led astray by those who, out of ignorance or interest, seek to reduce it to a proxy for Western influence.