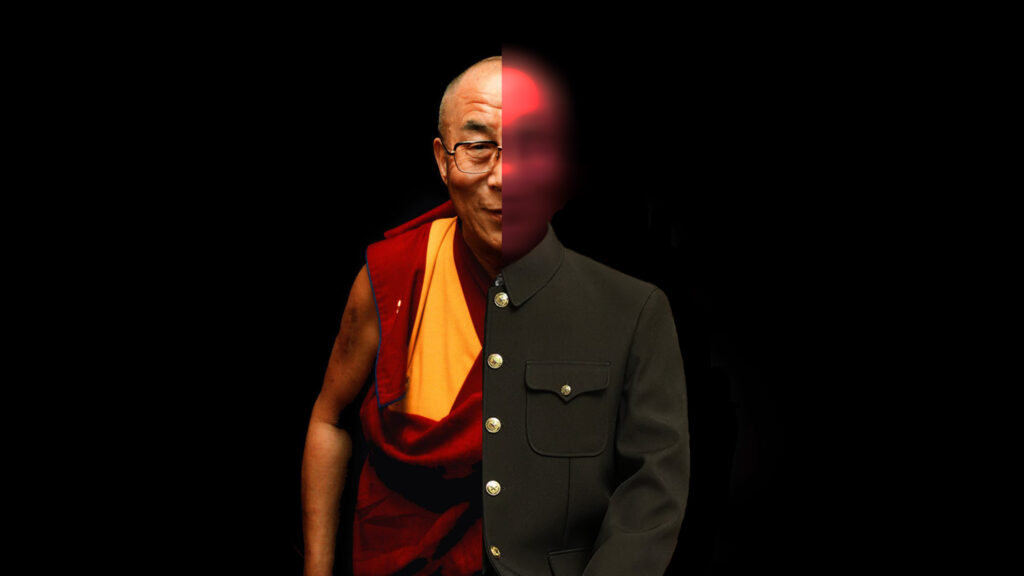

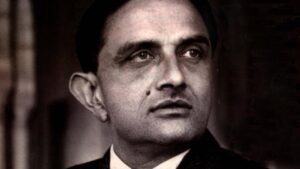

Homi Jehangir Bhabha, the architect of India’s nuclear program, died in a plane crash over the Swiss Alps in January 1966 while travelling to London. He had been a vociferous advocate of the testing of nuclear explosives, especial- ly in the aftermath of the first Chinese nuclear test in October 1964. With India’s humiliation in the 1962 Chinese invasion and the spectre of a nuclear China, a consensus had fast devel- oped in India for the wea- ponisation of the civilian nuclear program. Bhabha, a scientific genius and an influential man in both Bombay and Delhi who had been close to Pandit Nehru, pioneered the country’s nuclear program. He also led the lobby calling for an Indian bomb, which had grown both within the Congress and without.

It was in these circumstances, with political pressure from his own party and the opposition forcing Prime Minister Shastri, a resolute Gandhian pacifist, to consider the nuclear option and secure Bhabha’s backing, that both men died in highly unusual circumstances within thirteen days of one another.

Bhabha’s death has been particularly controversial for its circumstances and timing. The official reason given for the destruction of the aircraft carrying Bhabha, an Air India Boeing 707 named Kanchenjunga, was a collision with Mont Blanc, the tallest mountain in the Alps. The collision occurred when the pilot, believing he had flown past the mountain range, began his planned descent for a stop at Geneva.

In fact, the plane was still coming up on the Alps, and the descent drove it right into the mountainside. There were no survivors. Many doubt the official line, which cannot be confirmed because the plane’s blackbox was never recovered. Over the years, much evidence has surfaced to suggest foul play.

Soon after the crash, a journalist working for the French public broadcaster ORTF put together an expedition to visit the crash site from the Italian Alps to conduct an independent inquiry. Sure enough, evidence was soon found that directly contradicted the official narrative. One, a piece of wreckage that bore the date 1st June 1960. The Kanchenjunga had entered service only in 1961. Second, and most mystifying: a bit of fuselage made of a dissimilar alloy, extraordinarily light, a piece of what appeared to be armour, and camouflage-painted fragments. Based on the team’s findings, the French journalist, Philippe Réal, proposed that the aircraft was destroyed in a collision with a fighter jet flying a clandestine mission. Lending credence to this theory is another piece of wreckage preserved in a private collection in a French town near the crash site. This is a bent panel embedded with wiring, switches and brackets. Painted on it are numerical codes, and four letters: USAF, or United States Air Force.

French journalist, Philippe Réal, proposed that the aircraft was destroyed in a collision with a fighter jet flying a clandestine mission.

What these pieces, which might have belonged to a US fighter aircraft, were doing at the crash site has never been explained in the official account. But the collision theory isn’t the only one that competes with the official narrative. A number of people believe that not only is the official narrative false, it in fact a cover story for an assassination plot against Homi Bhabha. This view is supported most of all by the account of Gregory Douglas, an American journalist, of his conversations with a US intelligence operative named Robert Crowley. Douglas claimed Crowley told him:

“We had trouble, you know, with India back in the ’60s when they got uppity and started work on an atomic bomb…the thing is, they were getting into bed with the Russians.”

Referring to Homi Bhabha, he said

“that one was dangerous. He had an unfortunate accident. He was flying to Vienna to stir up more trouble when his Boeing 707 had a bomb go off in the cargo hold, And they all fell on a high mountain in the Alps. After that, no real evidence left, and the world became much safer ….”

Per Douglas’s account, Crowley went on to claim that the American Central Intelligence Agency, Crowley’s employer, also “nailed” Prime Minister Shastri, “another cow-loving raghead.”

“[Shastri was] a political type who started the program in the first place. Babha was a genius, and he could get things done, so we aced both of them.”

Many had suspected the involvement of foreign intelligence in Bhabha’s death for years before Douglas came out with his supposed conversation with Crowley. It is important to note that Gregory Douglas was a known conspiracy theorist, but in this case his alleged conversation with Crowley must be taken together with the material evidence.

An Indian nuclear bomb would have thrown a wrench in the strategic calculi of several powers vying for influence in South Asia and the Indian Ocean region, and would have further cemented India’s credentials as a leader of the Third World. Bhabha’s death silenced a firm and universally respected voice in its favour. Subsequently, it wasn’t until 1974, ten years after the Chinese bomb, that Mrs Gandhi ordered the tests at Pokhran. The long delay cost India vital security dividends and widened the strategic chasm with China. It also allowed Paki- stan under the zealous Zulfikar Ali Bhutto to begin in earnest its own long journey to the “Islamic bomb.” In 2023, India has suspended nuclear testing following the disastrous 2008 US Nuclear Deal, even as other nuclear-armed states conduct regular tests and work to upgrade and conventionalise their weapons.

1. Mont Blanc as seen from Planpraz station; 2. The Kanchenjunga’s wreckage

Bhabha’s death, which was of significant consequence to the overall security architecture of the region, is particularly suspect when taken together with the equally suspicious death of Lal Bahadur Shastri a fortnight before Bhabha’s, and that of Vikram Sarabhai, Bhabha’s successor in the Department of Atomic Energy, five years later. Sarabhai, who also founded ISRO, was 52 when he allegedly died ofcardiac arrest late at night in December 1971. The last person to speak to Sarabhai was APJ Abdul Kalam, then an up-and-coming rocket scientist. Sarabhai was cremated without an autopsy before his son could return from the United States to perform his final rites. Though individual theories compete for acceptance, there is a general sense that not enough has been done to probe these deaths as potential cases of foreign interference and that the government has downplayed their significance.

Vikram Sarabhai

Worryingly, the phenomenon of dying scientists and government apathy has persisted well beyond the 60s and the 70s. In 2009, a senior scientific officer at the Kaiga Atomic Power Plant in Karnataka went for a morning walk and never returned. His corpse was recovered from the Kali river five days later. His death was ruled to be a case of suicide. Later in the year, 20 personnel at the Kaiga plant were poisoned with tritium mixed in the drinking water. Though it did not result in fatalities, the poisoning incident did cause alarm over the state of security at the plant. Tritium is a radioactive isotope and is not easily accessed. Access to the area where the tritium was stored was meant to be heavily restricted. Upon investigation, it was discovered that several hundreds of unauthorised personnel accessed the area with master-cards. The CCTV footage from the area was lost due to not being backed up. Such a dismal state of security in a nuclear plant, a critical part of the nation’s strategic infrastructure, may shock many. In December 2009, two researchers perished in a freak fire in their lab at BARC. The lab was a kilometre from the BARC nuclear reactors. The researchers were not working with any inflammable material, according to a report in the Week dated July 18 2010. The report goes on to note that there were no fire extinguishers at hand and the fire truck got lost on its way to the lab, arriving 45 minutes late. Unfortunately, in safeguarding scientists working on critical technology, the state of affairs at Kaiga and BARC are the norm that prevails in India, rather than the exception.

Former Director of the ISRO Physical Research Lab and Space Applications Center Tapan Mishra was poisoned with arsenic trioxide in 2017. Mishra claims to have been poisoned twice. His case remains under investigation.

In October 2013, KK Joshi and Abhish Shivam were found dead in Vishakhapatnam, their bodies dumped on railway tracks and showing no signs of injury. The two men were chief engineers working on INS Arihant, the Indian-built nuclear-powered submarine. Despite their involvement in a sensitive defence project only a local police investigation was conducted, and as of 2023 the police have failed to find Joshi and Shivam’s assassins.

Responding to an RTI in 2016, the Department of Atomic Energy stated that there had been 70 unnatural deaths in its ranks in the preceding 8 years. The Bhabha Atomic Research Center alone accounted for 38 of these between October 1 2008 and October 1 2016, according to a report in the Sunday Guardian, the filer of the RTI. Causes of death ranged from drowning in the sea and getting run over by a train to death by hanging and even murder. Activist Chetan Kothari’s RTI petition in 2013 found that the deaths of 197 people working for various nuclear establishments between 1998 and 2013 had been ruled suicides. The suspicious deaths of personnel working in the nuclear programme, including those with knowledge of sensitive strategic projects, have been a matter of increasing concern over the years, but equally concerning is the silence of GoI on the matter. As in the case of the deaths of Homi Bhabha and Vikram Sarabhai, the deaths of largely anonymous nuclear scientists and other DAE personnel (the DAE did not disclose the names and designations of those who have died) have not been looked into as possible cases of assassination or sabotage. In certain cases, the families of the victims have faced the brunt of the ensuing investigation instead. The family of Partha Bag, one of the two BARC researchers who were killed in the 2009 lab fire, complained that the police questioning bordered on harassment.

Partha Beg & Umang Singh

From the Nambi Narayan affair, which derailed the Indian cryogenic

engine program, to senior ISRO scientist Tapan Mishra’s alleged attempted poisoning in 2017, the Indian space program has not been without its share of unusual occurrences either. In another petition filed by Kothari, ISRO was required to produce employee death statistics. ISRO reported the deaths of 684 employees, but did not reveal the causes of death. Mr Kothari’s petition eloquently surmised the tragedy of India’s counterintelligence and the complete failure of successive ministries in keeping the country’s top engineers and scientists safe:

“The most pressing issue isn’t who might be behind the murders, but that the Indian government’s apathy is potentially putting their high-value staff at even greater risk. Currently, these scientists, who are crucial to the development of India’s nuclear programs, whether for energy or security, have absolutely no protection at all.”