The United Kingdom is a country north of continental Europe that consists in the main of an island the size of Uttar Pradesh. It is known throughout the world for its capital city, London, which is a hub of global commerce and tourism, and its quaint monarchical government. However, a recent development in the island-nation has come to dominate the headlines in India, and that is the appointment of a new Prime Minister. The new PM, Rishi Sunak, had served as minister of finance in a previous ministry before being elevated to his current post by Charles II, the new King of that country, after he, Sunak, assumed leadership of the Conservative party, one of the two main parties of the UK, in October 2022. News of Mr Sunak’s appointment was received with great enthusiasm in India because of his ethnic background.

With roots in undivided Punjab, Mr Sunak’s family migrated to the UK from East Africa. Rishi Sunak, a graduate of the prestigious Oxford university and a practising Hindu, was himself born in the UK. A small, sprightly man with an animated face, Mr Sunak worked as an investment banker before entering active politics. He is married to the heiress Akshata Murthy, Infosys founder NR Narayan Murthy’s daughter. Aged 42 at the time of his appointment, Mr Sunak is the youngest British PM since 1812 and the first non-European person on the job.

Coverage of Sunak’s appointment has brought to the people’s attention other world leaders of Indian extraction. The list, to be sure, is extensive, ranging from the American Vice-President, Kamala Harris, who is an African-American lawyer with a Tamil mother, to the Irish former-PM and current Deputy PM, LeoVaradkar, whose father moved to the UK from Mumbai in the 1960s, and the Mauritian Prime Minister Pravind Jugnauth, a Hindu whose ancestors came from UP.

Another reason for the extensive attention paid to foreign personalities of Indian origin is the NRI (Non-Resident Indian) phenomenon, and the massive exodus of middle class India to greener pastures. Migration has in fact reached alarming levels. Annually, for every foreigner granted citizenship, 100 Indians surrender theirs.

1.6 lakh Indians gave up citizenship in 2021 alone. For comparison, during the Great Irish Famine, the average number of Irish emigrants was 2 lakh a year, only slightly higher than the current number of Indian emigrants. And where it was poor potato farmers who were forced to leave Ireland in the famine years of 1846-1851, mainly for North America, in the India of the 21st century it is paradoxically the relatively most prosperous upper- and middle-class that contributes the bulk of emigres.

In this situation, with the West receiving much of the migrant traffic out of India, political leaders like Kamala Harris and Rishi Sunak, or even business leaders like Satya Nadella and Sundar Pichai, the American CEOs of the tech giants Microsoft and Google, have become aspirational icons of the numerous Indian diaspora, and equally or perhaps more so for those in India who aspire one day to emigrate.

But if we look at this phenomenon objectively, can Indians justify the love-fest? Rishi Sunak considers himself a proud Briton, having excited some comment when he declared his enthusiastic support for England in the recently concluded World Cup. A senior member of the Sunak cabinet, Suella Braverman, born to Indian-origin immigrants from Kenya and Mauritius, once described herself as ‘a child of the British Empire,’ and considers the British Empire to have been, on the whole, ‘a force for good.’ Braverman also stated in her maiden speech as MP that ‘it is a stroke of luck to be born British,’ and has gained notoriety for her anti-immigrant views.

There is also Daleep Singh, former deputy NSA to US President Joe Biden, whose recent visit to New Delhi was marked by controversy. Daleep Singh is the grand-nephew of the first naturalised Indian expatriate to be elected to the US Senate, Dalip Singh Saundh. While in New Delhi, the younger Singh presumed to caution India on its Russia ties, saying “I don’t think anyone would believe that if China once again breaches the Line of Actual Control, Russia would come running to India’s defence.”

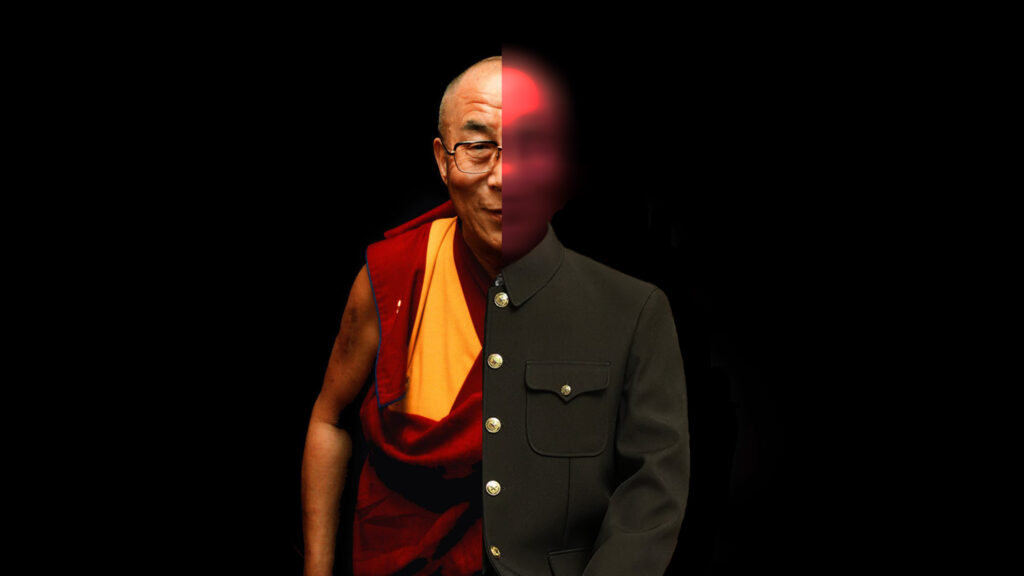

It is evident that foreign leaders of Indian- origin may only be trusted to act as agents of their country’s agenda, as they should. The expectation, the assumption, even, that they should somehow work for India serves only to create a vulnerability in Indian policy circles which they can, and do, manipulate to further their own respective national interests.

For this reason, the impact of Indian-origin politicians on India is, generally, negative. This is the case more broadly with Western intellectuals and academics of Indian-origin, who are engaging Indian audiences with greater frequency, in newsrooms and in opinion-pages, as India’s ties to the West increase. They constitute the spear’s edge of the diaspora’s engagement with India, with the final outcome being a muddling of India’s interests with the interests of the diaspora and its host countries in the minds of a certain section of Indian society, with several ramifications for policy-making in Delhi. Even as things stand, GoI has been engaged for years in lobbying for more permissive work- visa laws for Indians in the US, the UK and elsewhere, actively facilitating India’s terminal brain-drain in order to court lucrative NRI support. Unfortunately, the work-visa issue enjoys a total bipartisan consensus.

Taken together, these developments are cause for great concern. A lack of consciousness about who is Indian and who is not, and, in the globalised ethnoscape, of the infinite gradations that blur the lines between the two, has hurt India’s international position in the past and, exploited by the media circus (foreigners taking oaths on the Gita do make for excellent television), this blindspot may reliably be expected to hurt India repeatedly, and with greater effect, in the future.