Foreign Minister Jaishankar’s thundering rhetoric against selective outrage in Europe over India’s petrochemical trade with Russia turned him into an internet sensation overnight. The new rockstar of Indian foreign policy has made fans of India’s youth, a generation as curious and informed on the subject of international affairs as any that ever emerged in India. Perhaps the armies of public service hopefuls encamped at Delhi’s Karol Bagh and similar cram-school hubs around India also see their own future in the impeccably suited, smooth-talking career bureaucrat now in the prime of his life as minister. Judged on the fundamentals of India’s external affairs, however, Dr Jaishankar does not stand out in comparison to the ministers and prime ministers he served as public servant. That is to say, India’s geostrategic environment has not been moulded to better suit India’s security and trade interests to a degree that significantly distinguishes this government from its predecessors.

The ocean has been the greatest source of Indian power, and the cause of its greatest ruin. As an Indian Ocean power, India must contend with two vastly superior ocean-going forces: the American and the Chinese. Of these, China is the immediate threat to India’s desired position of primary Indian Ocean power. The Indian policy establishment believes the American strategic imperative to be in line with India’s. The truth that Indians cannot accept is that, of course, American foreign and defence policy derive from a calculus of needs and objectives wholly organic to the interests of American security and, equally importantly, American business. In short, India cannot marry its policies to those of the Americans the way the AUKUS countries, all Christian, Anglo-Saxon states, can.

The much-vaunted Quadrilateral Security Dialog is advertised as a game-changing alliance that is about to throw a wrench in the works of China’s growing military and trade empire. America’s stated unwillingness to engage in open hostilities with China means that at the same time as the alliance lulls Delhi into a false sense of security (where policy-makers appear to treat it as a substitute for Indian power projection capabilities), the Americans will also exert themselves upon the Indians to cede strategic ground to Beijing when American policy calls for it, and prop India up as a front-line state a lá Ukraine when the wind in Washington blows the other way. It is clear that the problem here is one of strategic autonomy, which is secured only on pain of equal or superior arms and strategic resolve vis a vis enemies and, especially, friends. A robust and modern Indian naval force based on the jutting launchboard of the Indian peninsula as well as on overseas bases on the East African seaboard, and friendly ports in Southeast Asia and the archipelago is the only thing that can sustain India in the Indian Ocean. American naval presence in the Indian Ocean is an established fact. It is possible and imperative, on the other hand, to control and restrict the rapidly expanding PLA Navy between the Malaccan chokepoint and the African Indian Ocean coast, the natural extent of Indian sea power throughout history. An Indian security architecture for the Indian Ocean, far from threatening regional partners, would be a welcome development for Japan and ASEAN countries, who are highly discomfited by China’s unchecked military expansion. A remilitarising Japan and a Vietnamese military used to punching above its weight will bring up the eastern end of the security architecture that would emerge in this way, completely imperilling the expansion that until now has been a cakewalk for China. All of it rests on the toughness and the will to lead in New Delhi, which of course is completely absent. Shinzo Abe tirelessly campaigned for a true vision of Asian security based on a strong India on one end and Japan on the other. But he was to die with only a toothless Quad to show for his effort. While in Japan Abe was opposed by habituated pacifists, in Delhi his pleas fell on pusillanimous and unimaginative policy hacks and politicians totally ignorant of hard power prerogatives in the conduct of foreign relations. No serious effort has been made by the Modi ministry to rectify India’s naval grand strategy (indeed to create one!) Endless diplomatic opportunities to shore up the support of our allies in pursuing Asian security comprehensively have also been squandered. The only policy innovation in this direction is the proposed sale of BrahMos missiles to Vietnam.

On land, first the British and then the Chinese decapitated this republic by the creation of Pakistan and the occupation of the Shaksgam valley. Denied its approaches to West and Central Asia beyond the Northwest Frontier and Ladakh, the right and privilege of the Indian nation and an avenue of intense commercial and cultural intercourse between India and its neighbouring states since the beginning of recorded history, the modern Republic of India has become a marginal power in the Asian heartland. Much was made of Gwadar, the Indian port on the Arabian Sea coast of Iran, east of the strait of Hormuz. But typical bureaucratic delays and acute fear of American chastisement have left this alternate route for India to its northern neighbors languishing. Without establishing direct lines of communication and trade, Indian diplomacy in West and Central Asia will at most be a sideshow to the Chinese steamroller steadily conquering the steppe up to Eastern Europe. While lack of political vision and will keeps the port at Gwadar inert, the Chinese have conducted their policy with the whole of northern Asia up to Europe in mind. Thus the Chinese state corporation COSCO has owned, among others, a majority stake in the Greek port of Piraeus on the Aegean Sea since 2016, bookending a network of infrastructure establishments throughout this region. While the Chinese Belt & Road program marches on, nothing has come of the North South Trade Corridor that was first proposed by Manmohan Singh. And now, as China, Russia and the United States build fleets of icebreakers to conquer the Arctic (which, if successfully done, will render the Indian navy’s potential hold on the Malacca straits obsolete by providing a polar route for the shipment of oil to China), the Indian state and its functionaries lie as inert and apathetic as ever, but now in style. Educated Indians must understand that grandstanding in international forums and dropping billion dollar defence contracts on state visits are not the elements of a functional foreign policy. The only thing that matters is aggressively securing India’s strategic interests as delineated above. And that must be the only criteria on which to judge every government.

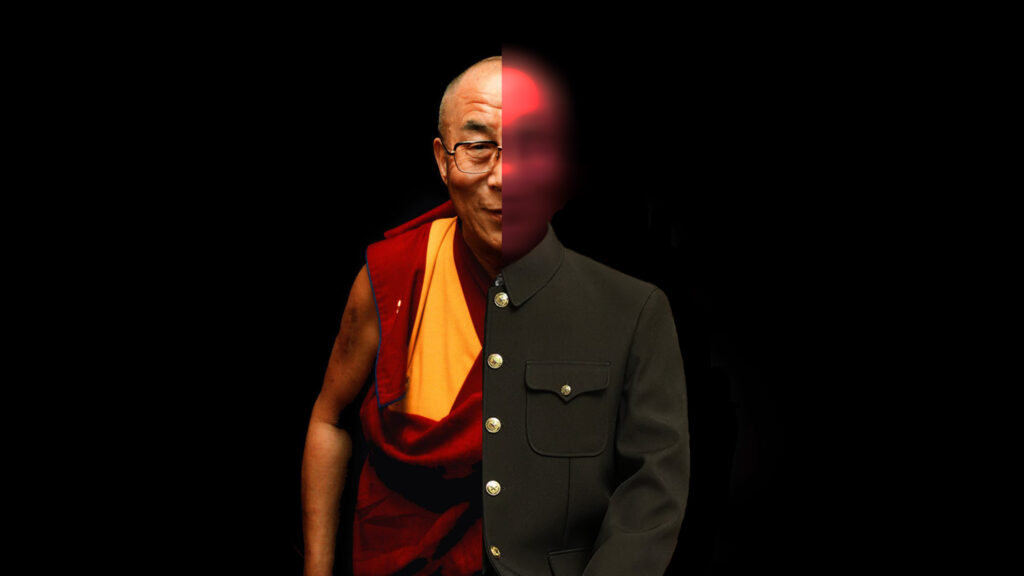

When viewing saccharine fluff pieces on PM Modi’s diplomacy and cheering the glamour and rhetoric of the Jaishankar brand of external affairs, clear-headed students of Indian foreign policy must keep these hard facts in mind. The cop-out that this government’s policies are still better, if only marginally, than previous ones may satisfy the rabble. Those who understand how the world really works will appreciate, however, that Jaishankar and Modi are delivering too little, too late. This fact cannot be obscured by sneering remarks at Pakistan and Bangladesh unless we wish this great country to be a rival of those failing states. The bottomline is that New Delhi’s directionless policy of latching onto one great power after the other, first the Soviet Union and now increasingly the United States, can no longer work. In the contest of powers in Asia, the Indian state must be driven under its own power or accept domination by more hard-headed players.