“The sovereign state has become obsolete,” Klaus Schwab told Forbes magazine in 1999. Schwab is the founding chairman of the World Economic Forum, and he has an impressive resume. Since its creation in 1971, the Forum under his chairmanship has spurred the creation of the World Trade Organisation and played a role in the unification of East and West Germany. It also brought together Nelson Mandela and white-minority president of South Africa FW de Klerk in 1992, and Israeli Foreign Minister Shimon Peres and Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat in 1994. More recently, the annual World Economic Forum held in the ski town of Davos, Switzerland, has become a mainstay in Indian television news.

It is attended by the chairmen and CEOs of one thousand corporations, typically with yearly turnovers in excess of $5 billion. The global elite descend upon the picture-postcard Alpine town to discuss global issues and create a common plan to deal with them. The businessmen also engage with journalists and celebrities and are courted by world leaders for investment.

About 250 business leaders like Anand Mahindra form the Indian contingent, in addition to ministers and chief ministers.

The Forum’s ambition has grown with its size and influence. It has programs with names like the Great Reset and the Global Redesign Initiative to create a new international order in which business interests participate equally in the affairs of nations. The immediate next step: giving multinational corporations a seat at the United Nations.

A report from openDemocracy, a London think-tank, notes that the Forum’s Global Redesign Initiative report “[calls] for a new system of global governing in which the decisions of governments could be made secondary to multitaskholder-led initiatives in which corporations would play a defining role.” It goes on to say that the WEF study recommended “a sort of public-private United Nations.”

The 600-page Global Redesign Initiative report, published by the Forum in 2009, outlines an ambitious plan to change who participates in global institutions and how.

The most crucial point in the report is phrased so vaguely it may be missed. It says that the Forum will benefit from “redefining the international system as… [a] multifaceted system of global cooperation in which intergovernmental legal frameworks and institutions are embedded as a core, but not the sole and sometimes not the most crucial, component.”

Simply stated, the Forum sees it as desirable for corporations to have legitimate presence in global institutions commensurate to and even surpassing national governments. But unlike the governments, which represent the sovereign will of their respective peoples, the corporations are not bound by any responsibilities except keeping their board members in the black.

Schwab’s belief in the obsolescence of the nation-state underpins much of the Forum’s work. In place of intergovernmental organisations like the UN, the Forum envisions a “multiple-stakeholder” system which will comprise private corporations alongside national governments. This system is supposed to be more dynamic and efficient in the process of getting the international community together to solve the world’s problems.

“The Forum is lobbying for corporations to have legitimate presence in global institutions commensurate to and even surpassing national governments

Though it argues for what it portrays to be a more inclusive global order, the comprehensive report fails to address that fact that the Global Redesign will totally circumvent the democratic process wherever it exists. Worse, it will further reduce the already-scant answerability that its constituent mega-corporations have to national governments by usurping some of the sovereign powers of those very governments. Harris Gleckman, senior fellow at the University of Massachusetts, USA, observes, “What is ingenious and disturbing is that the WEF multi-stakeholder governance proposal does not require approval or disapproval by any intergovernmental body”

“What is ingenious and disturbing is that the WEF multi-stakeholder governance proposal does not require approval or disapproval by any intergovernmental body”

A report from the Transnational Institute of Amsterdam also points out that 16 of its 24 board members are from Europe and North America, 22 attended European and US universities, and as many as 10 went to the same university, Harvard. Upon closer examination, the picture that emerges of the Forum and its plans is more of the old: a restructuring of world institutions to facilitate the concentration of power in the hands of a western elite, rather than the creation of the purported post-national 21st century world order.

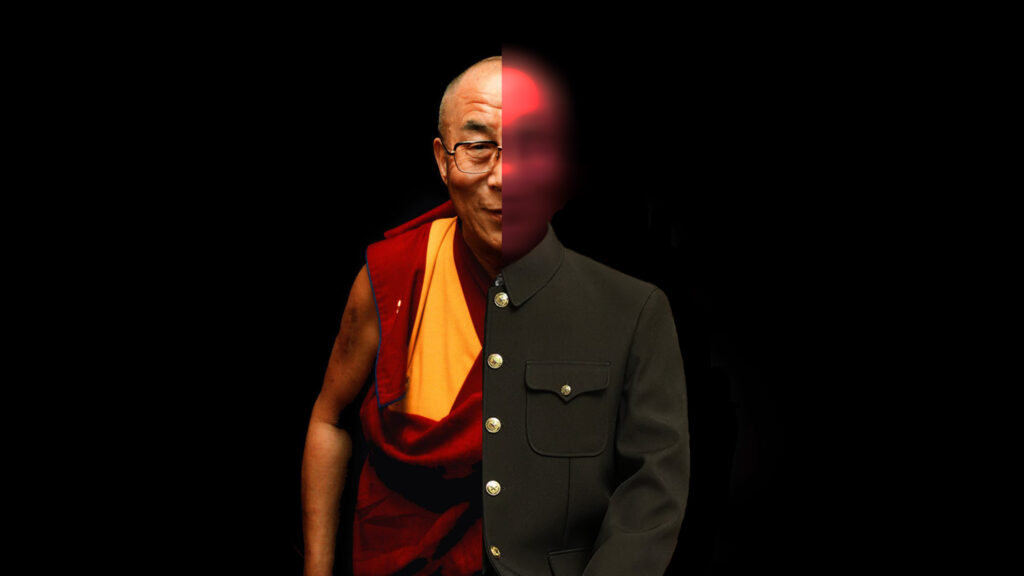

The Forum has 40 agenda-specific councils to solve various world issues. Interestingly, the solutions they recommend all typically include greater corporate interference, sometimes in very surprising areas. Take the example of the Agenda Council on Human Rights & Protection. Raising the spectre of hyper-nationalism, xenophobia, and human rights abuses, the Global Redesign report argues in one of its most stunning subversions that national sovereignty is no longer synonymous with national security. According to it, human suffering within fragile states, rather than wars between states, is the most pressing concern today. Human security within national borders is necessary for true international security, and to achieve it, the Forum envisions a multilateral system of global security which brings onboard non-state actors. The diagnosis is hard to argue with, but the solution, corporate control over sovereign affairs, is very obviously worse.

The Global Redesign report argues in one of its most stunning subversions that national sovereignty is no longer synonymous with national security.

This new public-private global security system may deploy ‘civilian capacities’ from the developed world to the fragile states of the developing world, in the way that militaries are deployed in war. The Forum suggests that these ‘civilian capacities,’ euphemism for government and administrative personnel, should be sourced from the private sector.

This program is termed in classical double-speak as “North-South partnerships for humanity.” It will create powerful corporate presence in the governments of some of the most vulnerable countries of the world. While the proposed international security arrangement raises obvious concerns about corporate influence in the developing world, the proposal is in line with the philosophy of the Forum and Klaus Schwab.

Schwab and influential members of the Forum like billionaire investor George Soros cite Austrian-British philosopher Karl Popper as their influence. Popper’s concept of the open society, set down in his WWII-era anti-totalitarian work The Open Society and Its Enemies, originally referred to a society that permits democracy, freedom and debate, as opposed to the closed society, which forbids discussion and questioning the state.

Presently, in addition to lending its name to Soros’s Open Society Foundation, the open society has become a byword for the corporate-globalist vision propounded by the Forum, which is a vision of a world in which multinational corporations and their leaders have an increasingly prominent role in international relations, equalling or exceeding the role of national governments. The role of the sovereign state is greatly diminished, as are national borders and identities.

The “open society” has become a byword for the corporate-globalist vision propounded by the Forum, which is a vision of a world in which multinational corporations and their leaders have an increasingly prominent role in international relations, equalling or exceeding the role of national governments.

In 2019, the world got a glimpse of the order outlined in the Global Redesign Initiative report. On 13 June that year, the United Nations quietly entered into a Strategic Partnership with the Forum, taking the first step toward the new public-private UN.

Following the Strategic Partnership, the UN Secretary General has made several references to the ‘multi-stakeholder’ principle. In the Secretary General’s Our Common Agenda report in 2021, which laid down the roadmap for the UN over the next quarter century, the importance of ‘multi-stakeholder engagement,’ essentially corporate involvement, was emphasised in order to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Secretary General Guterres then attempted to sidestep a conference on the SDGs entirely, proposing a late-2023 Summit of the Future in its place. Predictably, the Summit of the Future was to be a “multi-stakeholder group” (MSG) event, inviting the presence of corporations. But the response of the majority of UN member states to this move was unified and decisive in its resistance.

This came in the form of a Group of 77 intervention. The Group of 77, a group of low- and middle-income countries at the UN, including India and China, made an intervention to stop the Summit of the Future and force dialog on the SDGs instead.

However, this is just one instance of visible concerted action, compared against years of quiet work by corporate interests inside and outside the Forum to firmly entrench multi-stakeholder groups, more accurately corporate cartels, in international relations. They constitute the leading edge of the Global Redesign, a steady build-up of corporate presence in international forums. Of particular concern, Gleckman’s report points out, is the UN Security Council’s push for public-private partnerships (PPPs) in warzones. Similarly, UN chief Guterres sponsors UN-business partnerships in the energy sector, and countries of the world call on MSGs to solve the ‘technical’ problems of capital flow to the developing world. Though in their present form these corporate-public working groups do not pose a challenge to traditional international decision-making processes, based on the cooperation of sovereign states, they have also laid the groundwork for greater corporate intervention in the future.

The Forum’s consistent efforts to integrate corporations into this new ‘multi-stakeholder governance’ system have not been given serious attention. It is a silent takeover, and it will continue as long as it escapes serious governmental action around the world. More actions like the intervention of the Group of 77 are necessary to contain the quasi-governmental ambitions of the Forum and various MNCs. Without concerted action, Schwab’s words will become prophecy as the multi-stakeholder governance principle being pushed by the Forum encroaches upon the sovereign functions of national governments. When a government stops working in the interest of its people, it can be reigned in by civil society or changed by the electorate. In the worst case, it is overthrown. But the global corporation knows no checks outside the company board, and it knows no mandate other than creating and consolidating wealth, often to the detriment of its workers and the environment. The architects of multi-stakeholder governance might or might not be sincere in their stated goal of creating a fairer and more efficient world order, but to most observers it is a systemic restructuring of world organisations to emplace powerful multinational corporations snugly at the centre of international relations. The World Economic Forum is working behind a smokescreen of equitable world governance to hand more power to the corporate elite. They are allowed to do so at the peril of the world’s most vulnerable in the short-term, and by endangering the freedom of all sections of society over time.