On Thursday, October 31, in an oddly lighthearted scene, Chinese and Indian soldiers, having been stationed in a tense standoff in the Himalayas for the past four years, exchanged candy at several points along the border in celebration of Diwali. This demonstration of friendliness followed the border agreement announced by India on October 2 and addressed the restoration of patrol and pasture rights along a section of the 3,488-kilometer demarcation line. Bhutan and China, on the other hand, have been holding yet-unresolved border talks for decades. Looming in the backdrop of those discussions is India, China’s biggest regional rival and Bhutan’s close diplomatic ally. The nuclear-armed neighbors have previously gone to war and more recently engaged in a series of skirmishes over their disputed 2,100-mile border, which straddles Bhutan – and, in Beijing’s eyes, makes the small Himalayan nation all the more critical to its national security.

High in this mist-shrouded Himalayan nation, a winding mountain road opens to a clearing in the pine-forested valley, revealing rows of uniform Tibetan-style houses, each topped with a Chinese flag. “They are building resettlement houses here,” said the Chinese travel vlogger who captured these scenes last year, speaking into his phone on a roadside. “When people live and settle here, it undeniably confirms that this is our country’s territory.” But the village – known as Demalong and formally founded in March last year with a community of 70 families, according to a government notice – is not only located in territory claimed by China but is also one of a string of Chinese settlements within the border shown on official maps of Bhutan. For centuries, herders looking for summer pastures were the main presence here, but now, there is a growing population as the Chinese government incentivizes hundreds of people to settle there from across Tibet.

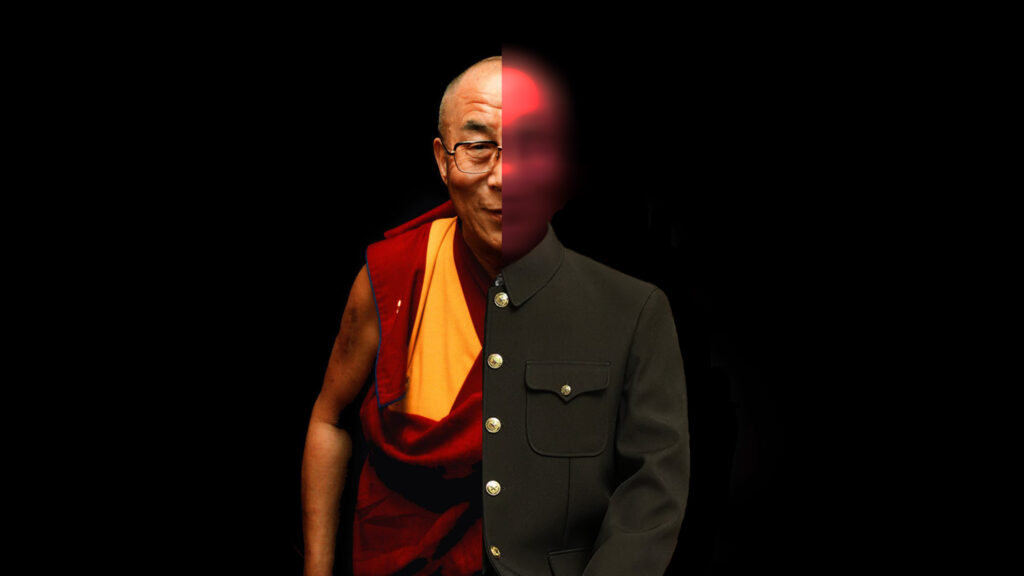

Those settlements show another, quieter front in China’s expanding efforts to assert its control over disputed, peripheral territories – also playing out in the South and East China Seas – as China seeks to bolster national security and enhance China’s position over its rivals. Bhutanese authorities, however, have repeatedly rejected previous reports of Chinese encroachment, including in a foreign media interview last year when then-Prime Minister Lotay Tshering “categorically” denied that China had been building in Bhutan’s territory in the northern district of Lhuntse, where such villages were identified. “China’s construction activities in the border region with Bhutan are aimed at improving the local livelihoods,” a ministry statement read, “China and Bhutan have their claims regarding the territorial status of the relevant region, but both agree to resolve differences and disputes through friendly consultations and negotiations.”

New research by a team led by the School of Oriental and African Studies, or SOAS’ Barnett, extensively tracks the Chinese construction of what the researchers classified as 19 “cross-border villages” and three smaller settlements since 2016. The construction has taken place in border regions in northeast Bhutan and the west of the kingdom – near the disputed border between India and China, according to the research. “China, as the most powerful player in the relationship, seems to be experimenting whether it can more or less decide for itself whether or when it is entitled to take ownership of territory disputed with a neighbor … and how and if the international community will respond,” Barnett commented.

Myanmar Leader in China

LP Bureau New Delhi

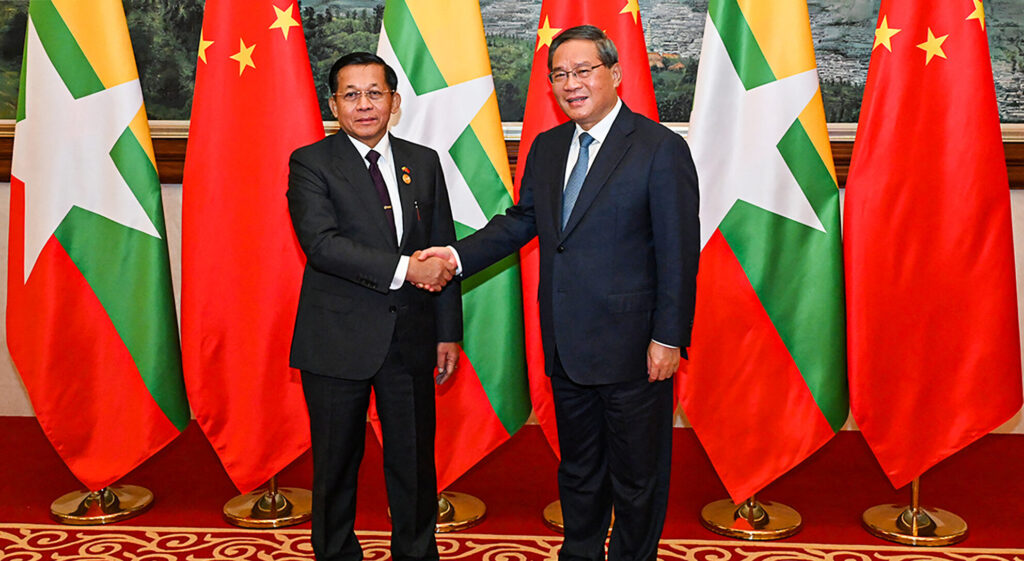

Min Aung Hlaing, Myanmar’s junta chief and acting president who’s facing the recently issued ICC arrest warrant, paid a long-due visit to China on November 6. Although it was not a State visit, it was a significant three-day visit to Southwest China’s Kunming City, with Myanmar attending the eighth ‘Greater Mekong Subregion Summit’ from November 6-7. It was on the sidelines of the summit that he met Chinese Premier Li Qiang and other key figures. While this may seem like a long way from China’s endorsement of his anarchy-ridden management of a post-coup Myanmar, it does suggest that Beijing sees him as a crucial player in the context of conflict resolution there.

China is not just Myanmar’s neighbor and an important ally, but also Myanmar’s largest trading partner; with the Yunnan province especially, where the minor summit of countries occurred, being at the receiving end of refugees and trade disruptions owing to hostilities across the borders with Myanmar. This visit is also significant in the context that this may very well be seen as his first ‘major’ appearance at any regional gathering in the recent past, owing to the fact that the embattled leader has been shunned by the regional gatherings which are usually attended by Burmese leaders.

The few overseas trips that he has made since 2021 have been to Russia, now a staunch ally. China always takes the symbolic importance of diplomatic protocol seriously and was likely very conscious of the signal sent out by Min Aung Hlaing’s presence there.

China and Russia have always played a critical role in fomenting, enabling, accelerating, and ‘stopping’ coups. China and Russia have enabled militaries to launch and sustain coups or have helped militaries become involved in domestic politics in other ways. And this matters, especially in the context of the observations over the past year which suggest that China might be preparing to wash its hands of Min Aung Hlaing, as the civil war has been becoming increasingly costly for Beijing.

The ethnic insurgent alliance which has inflicted great damage to the Myanmar military operates along the border with China and launched its offensive a year ago with the declared objective of shutting down scam centers of which thousands of Chinese citizens had become victims. It was thus widely presumed that China, frustrated by the junta’s refusal to act, had given the insurgents a green light to move in and do so. In recent months, China has taken steps to mitigate the ongoing instability in Myanmar, with the primary goal of preserving the military regime. Beijing is urging the junta to establish a clear roadmap for democratic elections, facilitate the resumption of cross-border commerce, and ensure the protection of ambitious Chinese investments in the region.

Numerous resistance groups in Myanmar have categorically rejected any dialogue with the military junta, advocating for a fundamental transformation of the political landscape. The NUG, the rightful government deposed by the coup, has criticized China’s invitation to Min Aung Hlaing as a tacit endorsement of the illegitimate regime. China, recognizing the limitations of Western influence in this region, has opted to work with the junta, regardless of its human rights record and governance failures.

India, another potential giant influence, has busied itself with localized border issues with Myanmar.

Myanmarese drug trade growing in India

Aishi Mitra New Delhi

Three individuals, including a Myanmar national, were arrested in Champhai district, Mizoram, on November 7th for alleged involvement in drug smuggling and possession of contraband. A joint operation conducted on November 5th by Assam Rifles, Mizoram Excise, Narcotics Department, and Customs Preventive Force in Zote village led to the seizure of 128 grams of heroin and areca nuts valued at approximately Rs 1 crore.

The arrested individuals were identified as Nangkhawkhupa (30) and Ruatfela (36), both residents of Aizawl, and LT Siama (39) from Myanmar. All three were handed over to the Excise and Narcotics Department in Champhai for further investigation and legal proceedings.

But this isn’t where the recent entanglement of Mizoram and Myanmar’s narcotic fate ends – in the first two weeks of November, it was discovered that Indian smugglers and their local contacts on either side of the international border used excavators to carve out a 10 km long “jeepable road” in Myanmar for the ‘Dawn’ of a new drug route through Mizoram, officials said.

Dawn is the name of the nearest habitation from Lungkawlh, a village in central Mizoram’s Serchhip district situated near the border with Myanmar. Moreover, on November 20th, in a significant haul of drugs in Mizoram, the Assam Rifles and state police jointly seized 28.520 kilos of methamphetamine tablets, 52 grams of Heroin worth 85.95 crore, and a foreign pistol in three separate operations in Champhai district, bordering Myanmar.

Varied drugs, especially heroin and methamphetamine tablets, also known as party tablets or Yaba, are often smuggled into India from Myanmar, which shares a 1,643-km unfenced border with four northeastern states – Arunachal Pradesh (520 km), Manipur (398 km), Nagaland (215 km) and Mizoram (510 km).

India’s Northeastern Region (NER) has long been a victim of drug trafficking, a problem exacerbated by its proximity to the Golden Triangle. The unfenced, porous border with Myanmar allows for the easy influx of narcotics into India, with devastating consequences for the region’s socio-economic well-being. Myanmar’s role as a major global producer of opium and heroin, globally second after Afghanistan, coupled with its strategic location within the Golden Triangle, makes it a key player in the regional drug trade.

Organized crime syndicates, ethnic militias, insurgent groups, and military factions, often intertwined, exploit the region’s porous borders to facilitate the smuggling of drugs, arms, and people.

In 2023, Myanmar became the world’s top opium producer, with illicit crop cultivation expanding from 99,000 to 116,000 acres. This rise has intensified the threat of drug trafficking in the NER. In FY 2022-23 alone, contraband worth over US$267 million was recovered in the NER states.

There is a need for steadfast cooperation and coordination between national and international law enforcement agencies to curb the transnational syndicate. To this end, India and Myanmar have certain mechanisms in place but have failed to arrest the drug trade. A superimposed border, the Free Movement Regime, lackluster border surveillance, and the topographical proximity of the borders of the NER states and Myanmar make the borders even more permeable for the ‘free movement’ of drugs.”