The Chinese government maintains one of the world’s strictest media blackouts in Tibet, a unique nation in the heart of Asia that China invaded and occupied soon after the Communists came to power. The annexation of Tibet is part of China’s Five Fingers plan of conquest, which articulates the CCP’s intent to invade and occupy three Indian states and two Himalayan nations: Ladakh, Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh, and Bhutan and Nepal.

Now, China has turned Tibet into one of the most restrictive places in the entire world for press freedom. Information of any kind is tightly controlled or erased: foreign journalists are essentially banned, and Tibetans who speak with outsiders face persecution. The most fascinating fact is perhaps that Tibet’s core, the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR), is the only Chinese province requiring special permission for any reporter to enter, and in recent years, every journalist who applied has been turned away. The only access allowed is through official “press tours,” where guides use intimidation and propaganda to ensure visitors see exactly what the Party wants, akin to what a hundred speculative fictions have already warned us about.

But, in true testament to human resilience, against this iron curtain, Tibetans in exile have built media networks. Independent news agencies based in Dharamsala and elsewhere stitch together insider reports from Tibet through clandestine channels. Sources inside Tibet relay eyewitness accounts to trusted monks or residents called communicators, who then pass verified information to Tibetan exiled journalists. This dispersed network – comprising sources in Tibet, hidden intermediaries, and exiled Tibetan reporters – has become a lifeline for Tibetans living under occupation. In India, which has hosted hundreds of thousands of Tibetan refugees since the first days of the Chinese communist invasion, independent news media produce and disseminate real, unfiltered news from the homeland. In practice, exiled outlets publish bulletins, websites, and broadcasts in Tibetan and Chinese, keeping the world informed. In India, the exiled Tibetan community has found an unlikely newsroom to keep telling the stories of their struggle to the world.

But this digital lifeline is dangerously fragile. Tibetan journalists rely on ordinary technology like phones, social media, and Chinese-owned apps to share information. This reliance on ICTs (Information and Communication Technologies) owned and operated by Chinese companies just means that they are vulnerable to government censorship and surveillance: the very institutionalized system that they are trying to bypass. In recent years, Chinese authorities have rapidly increased online repression in Tibetan areas. Since 2021, at least 60 Tibetans have been arrested for innocuous acts like sharing photos or videos on WeChat or TikTok. Many were charged with possessing “banned content” – in practice, anything related to Tibetan Buddhism or the Dalai Lama. One man was jailed for creating a WeChat group to celebrate old monks’ birthdays, and others were imprisoned for posting poetry or music in Tibetan. Chinese police have even conducted mass phone sweeps, using mandatory monitoring apps to turn personal devices into governmental tracking tools. This creates a constant fear: one radio interview or photo upload can mean a night in detention or worse.

The crackdown, beyond just physical seizing, extends even to culture and language. Beijing has explicitly targeted Tibetan identity online. Late last year, Douyin abruptly banned all Tibetan-language content and any and all content that related to Tibetan culture and identity. Since the Chinese constitution nominally guarantees minorities their language, Tibetans are left to protest this ban as illegal. Other platforms, from Bilibili to Talkmate, have similarly barred Tibetan scripts. In short, Tibetans cannot safely share their own art, stories, or teachings online. Many activists describe this as part of Beijing’s campaign of cultural genocide, an attempt to assimilate Tibet by destroying its language and traditions.

In the face of such repression, the Tibetan exile community and its Indian supporters must tread a fine line. On one hand, India has become a haven for Tibetan culture and journalism. The government of Tibet, called the Central Tibetan Administration, regularly holds press conferences and issues statements exposing Chinese abuses. For the several hundred thousands of Tibetan refugees who live in India, radio and newspapers operate freely, broadcasting in Tibetan. They also broadcast deep into occupied Tibet. To those living in repression in Tibet, these broadcasts hold the symbolic value that Radio Free Europe once did for those living under communist rule in Eastern Europe. Operating from India and across the free world, the Tibetans are now telling their stories of repression to international audiences that otherwise would hear only Beijing’s version of events.

Some in the Indian media and government stand accused of pushing back against the free speech and media activity of the exiled Tibetans. Experts in India have warned that some in the Indian media are propagating the Chinese narrative on Tibet. After official China-sponsored trips to Lhasa, they have uncritically echoed Chinese language and propaganda by calling Tibet by its Mandarin name “Xizang” and praising how ‘Xizang has done well under the CCP,’ China expert Sriparna Pathak said in an interview to the China Media Project. Such terminology is not a mere matter of words: it echoes Beijing’s claim that Tibet is inseparable from China. This is, in short, also a security threat for India. By normalizing “Xizang,” India risks validating China’s claim to Arunachal Pradesh as “Zangnan” (“South Tibet”). This linguistic sleight of hand undermines India’s sovereignty and fuels Tibetan fears. In an ANI report from January, Tenzin Phakdon of the organisation Students for a Free Tibet was quoted as saying, “It is very sad to see not only China but then some paid Chinese media and also some of the major media in the world using Xizang instead of Tibet.”

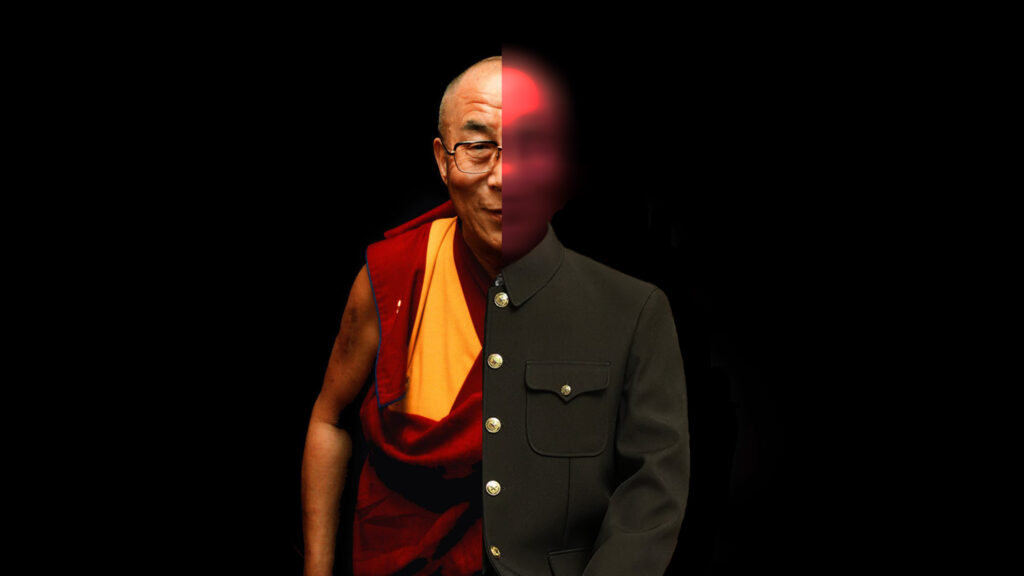

Kowtowing to Beijing is not a new development in the Indian media or the political establishment. Caving to pressure from Beijing, India has sometimes limited its own journalists and diplomats in Tibetan matters. For example, in 2009, the Indian government canceled visas of foreign reporters to avoid offending China ahead of a Dalai Lama visit to Arunachal Pradesh. That decision drew public criticism from Tibetans. More recently, India and China have expelled each other’s journalists amid border tensions, leaving even less on-the-ground reporting. While India hosts the Dalai Lama and allows free assembly of Tibetans on its soil, it also stays vague on Tibet’s status to avoid diplomatic fallout. Despite China claiming significant parts of India and Bhutan as Chinese territory, and also recognising Indian territory as part of Pakistan, the Indian government arbitrarily affirmed the legitimacy of the Chinese occupation of Tibet by recognising the nation as a Chinese province in 2003. This ambivalence constrains the free flow of Tibetan news and shapes Indian media narratives.

Meanwhile, China’s censorship in Tibet respects no boundaries, not even natural disasters. In January 2025, a 7.1-magnitude earthquake struck Dingri County in western Tibet. Tens of thousands of people were affected, yet the Chinese government moved swiftly to control the narrative. 21 Tibetan social media users were summoned and punished simply for sharing updates about the quake. Police banned them from livestreaming and accused them of spreading false information when local death tolls exceeded official figures. In one case, a Tibetan woman was forced to shut down her TikTok account after posting earthquake footage. All related videos and photos in Tibetan were scrubbed from Chinese platforms. An “internet clean-up” in the aftermath of such a tragedy underlines how deeply Beijing fears any independent Tibetan voice.

The image of censorship in Tibet is something like this: no unsupervised foreign reporter inside; all local media organs controlled by the Party; key words and language erased from cyberspace; everyday Tibetans jailed for a song, a post, a prayer. The costs are human: prisoners endure torture, and ordinary families dare not speak openly. One monk, Losel, from Lhasa’s Sera Monastery, was beaten to death in custody in 2024 after being detained for ‘collecting and sending information abroad.’

The Free Tibetan government has appealed for international condemnation and oversight, stating that these cases “underscore the need for accountability and respect for the fundamental rights and freedoms of the Tibetan people”. Tibet’s story is not isolated. In other conflicts – Myanmar under junta rule, Syria under Assad – exile journalists and activists built international awareness through networks and the internet when home media were muzzled. That history shows it is possible to pierce the veil of silence, but only if the outside world listens. India, in particular, is at a crossroads. With great fortitude, Tibetan exiles have found a new life in India’s democratic society. For new generations, the dream of a free Tibet is still alive, and India is the only home they have known. India has both opportunity and responsibility. It must protect the freedom of the Tibetans in every sphere, including protecting the organisations bringing news out of occupied Tibet.