When the British began teaching us English, they put the capstone on a thousand-year process of scrambling the Indian brain. Learning and high culture have flowed down from the Latin and Greek corpuses into the Germanic, Romance and Slavic languages of modern Europe and formed the bedrock of Western civilisation.

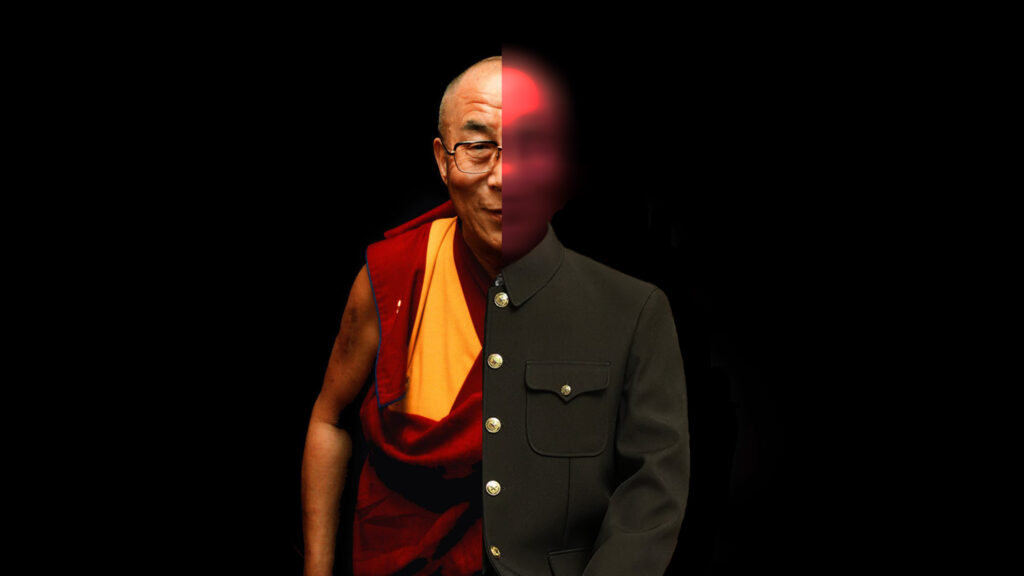

In upper India, Sanskrit and the prakrits followed this trajectory until the Persianate age. The period of Islamic rule over India was presided over by dynasties, Muslim and Hindu, who were either Persianised in character or had expended all their energies in resisting that fate. Even at this stage, the literary and philosophical traditions were Indian, though variously influenced by and adapted from the Persianate and Islamic scenes. But European colonisation was completely different in nature, proceeding in the age of rapid globalisation and early modern communications. The superlative Royal Navy and British merchant fleets, the telegraph, and the printing press helped magnify and entrench the European presence on the Indian continent as much as any rifle or cannon. The intent of the British differed from previous conquerors too. Having settled their territories in India, and shaken by the First War of Independence in 1857, they anticipated contemporary technological corporations in identifying the human mind as the next frontier for conquest. Macaulay’s role in the following process of Anglicisation in India is well-known. But by holding up Macaulay and other colonial figures, their Indian lackeys and successors as the bogeymen of Indian cultural decline, critics can offer nothing constructive. It is pathetic in the extreme for the conquered to expect any treatment from the conqueror that is not of the conqueror’s choosing. It is also bad strategy. It is the imperative of the conquered to apply such power as they possess in absolute resistance, without regard for success or extinction. That was the way of the Americans, the Haitians, and many other colonised nations that successfully fought against worse odds than we ever faced. The coward’s way of compromise and negotiation with the conqueror has given India, in the case of language, the obscene feebleness of modern Indian society. The introduction of the English language has degraded the literary and intellectual character of the Indian nation in ways that we will be discovering for a long time once an honest account of the state of Indian society is begun at any significant scale. But in essence, it has divorced thought from reality. The educated Indian cuts her teeth on the stories, philosophies and politics of an alien world. Parallel consciousnesses tear at her person. Her life becomes a long act of interpretation and adaptation, wasting her faculty for creation and origination. In the long arc of modern Indian history, it would not be remiss to state that India’s genius has been spent on translation, from the West and for it.

In the long arc of modern Indian history, it would not be remiss to state that India’s genius has been spent on translation, from the West and for it.

Sri Aurobindo saw the spirit of India wilt in the Anglophone age like no other did then or has done since. “The sap soon began to run dry, the energy to dwindle away. Worse than the narrowness & inefficiency, was the unreality of our culture. Our brains were as full of liberty as our lives were empty of it,” he wrote in 1907. “The very sights & sounds, the description of which formed the staple of our daily reading, were such as most of us would at no time see or hear.” His words are truer today than they were then, because the fig-leaf of British rule that gave some dignity to India’s surrender to English has been snatched away now, with entire generations having lived and died since Independence. “We looked to sources of strength and inspiration we could not reach and left those untapped which were ours by possession and inheritance.”

Works of postcolonial history and sociology that do understand some aspect or the other of the ruin we face are dense and impenetrable, and they are not meant for the lay Indian, or any non-specialist, to read. Nor do they offer any solutions. Their authors are as irrelevant as the half-literate ideologues of various stripes who scream in favour of adopting one single national language or the other. They reduce the sublime process of becoming that a people and its language undertake to a bureaucrat’s decision, to be forced upon India as English was. The solution cannot be decreed from on high. It must originate at the source of the contradiction, the Indian’s mind.

We looked to sources of strength and inspiration we could not reach and left those untapped which were ours by possession and inheritance.

The muckraking over regional languages and the polemics against colonial figures being published several centuries too late are, above all, a way to escape responsibility for the crime (I do not use that word lightly) that generations of Indians have committed against their ancestors and their descendants. Their crime is the unresisting, even willing, adoption and use of English. The equal and reverse of this positive surrender is the proven impotence of Indian-language literatures, especially the Hindi, in attracting and keeping the attention of all Indians excluding the most involved and self-conscious literary types. I daresay no child ever hid under her blanket with a torch to devour Premchand or Rahul Sankrityayan deep into the small hours of the night. Hindi may not lack great works, but nothing in Indian education or culture can prepare young readers, who are necessarily the living soul and salvation of any language, to reach them. What Hindi has to offer is not even a sliver of the dizzying English register. A hundred government-sponsored literary conferences count for nothing against that failure. No Indian writer, save exiles and expatriates to the West, can pretend to participation in a real, consequential literary movement in living memory, but I will concern myself only with Hindi, which is the most widely-spoken language in India, and the third most important language in the world. Entrusted to professors and socialites, like Indian English also is for the most part, literary Hindi languishes in the smallest bookstore corners. What we have to show for three quarters of a century of Independence, if those bookstore shelves are anything to go by, are beautiful leather-bound Gitas and translations of Rich Dad, Poor Dad and The Monk Who Sold His Ferrari. Hindi cinema has demonstrated the potency of the language when it is used with clear intent and in service of the creative motive. The same cannot be said for Hindi literature. Agyeya, Sankrityayan and others saw the problem clearly, and their literary efforts were heroic. But they were not enough. Sensitivities were high in the decades leading to Independence and the greatest minds of the country were preoccupied by what appeared to be more pressing issues in the byzantine ideological landscape of the Independence movement and its aftermath. But there can be no doubt in any mind, the language question remains the most important to India. The Indian elites aspire to become a larger Singapore. Participants in this unconscious movement toward total surrender must be resisted with extreme prejudice. We cannot be a country totally deracinated and cut off from the wellsprings of our identity. If India continues to sleepwalk into the role of an inferior hanger-on of the Anglosphere, with its sights set on the most unworthy, materialistic goals that even Western thinkers are now beginning to resist, all the struggle and sacrifice of the greatest Indians of the past centuries will have been for nought. If one recognises these self-evident truths and the urgency with which they must be acted upon, one must accept in principle that taking back our language is where we begin. This applies equally to all the great languages of India. And for the largest number of Indians, nothing short of the development of a new Hindi literature can begin a true movement of resistance to India’s total psycho-social domination by English.