The new White House paper on national security strategy, released in November, would have elicited very different reactions from the Kremlin and from Zhongnanhai, the seat of the Communist Party in Beijing.

Trump has been explicit in expressing his intent to change long-entrenched precepts of US foreign policy, particularly in its treatment of Russia and China. For decades, the US foreign policy establishment had pursued a policy of positive engagement with China, based on the expectation that close economic cooperation with the West will affect the Chinese positively, encourage Beijing to collaborate in a “rules-based international order” and slowly soften the totalitarian regime in that country. Underneath the rhetoric of optimism— informed in the 90s by a mood of post-Soviet neoliberal triumphalism, which made the victory of Western capitalist democracy against other political systems appear to be a matter of when rather than if— lay the Kissinger-era policy of cultivating China as an anti-Soviet bulwark and a partner in shaping the world order. This strain of American China policy was never expressed as unabashedly as during the Obama administration, when Zbigniew Brzezinski, a key figure of the US foreign policy establishment who conducted secret negotiations with the Chinese to normalise relations in 1978, made the outright call for a US-China G-2, or Group of 2, to preside over the international order, the US and China being the chief “status-quo” and rising powers respectively.

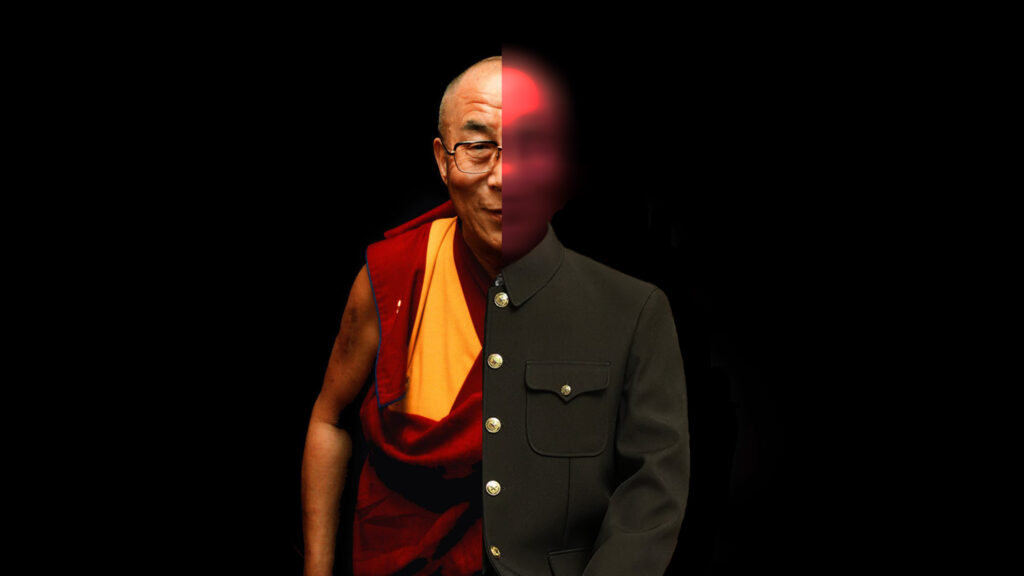

It took until Trump in 2015 to begin uprooting the Cold War policy of appeasing China, but the facts on the ground had shown the Kissingerian framework to be a failure almost as soon as it was put in place. For a brief moment in the 80s, China appeared to be headed for a cultural and political transformation to accompany Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms, until the Tiananmen Square massacre declared to the world that the Communist Party intended to rule as before. Xi Jinping has shown more clearly than any previous Chinese leader that the Party always intended to take every economic benefit it could from hopeful global partners, but to apply the accruing economic muscle only to strengthen and expand the totalitarian Chinese order within and beyond its borders. Beijing has benefited enormously from policy doves in world capitals, including New Delhi, harping on the unexamined prediction of economic collaboration leading to diplomatic thaws and Chinese participation in an equitable world order, and continues to do so as it builds economic influence and hard military reach on all continents.

In a stark break with past administrations, various strategic and foreign policy documents emanating from the Trump White House and the US Department of War (previously the Department of Defence) have now acknowledged the Chinese as strategic rivals.

The 2025 National Security Strategy has committed the United States to “[building] a military capable of denying aggression anywhere in the First Island Chain,” referring to the arc of Japan, Taiwan, the Philippines and Borneo that stands between the Chinese mainland and the rest of the Pacific, along with the Second Island Chain that extends to Guam, Palau and New Guinea. It also delineates plans for the US to lessen dependence on products coming from China and Chinese factories across the world to address trade imbalances that have resulted from legacy economic policies. In both the economic and defence spheres, the Trump administration wishes to rope in partner nations across the world and acknowledges Chinese influence on emerging economies as a strategic threat. For Europe to follow suit, the US sees the end of the Ukraine war and for Europe to “reestablish strategic stability with Russia” as contingent.

“The adjustments we’re seeing… are largely consistent with our vision,” commented Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov in an interview to Russian state media. Trump’s outreach to Russia was hamstrung by the 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Now, with negotiations for peace gathering pace, Trump has voiced his support for the end of the war and for the nations of Europe to reengage the Russians, apprehending negative effects on Europe from “external dependencies,” especially upon Chinese industry, that have been created by Russia’s estrangement from the continent.

Comments on European affairs in the National Security Strategy did not go down well in European capitals. It includes references to confusion created by weak minority governments, the centralisation in the European Union of sovereign policy imperatives including immigration, and the threat of demographic change and “civilisational erasure” weakening transatlantic ties, particularly with the UK and Ireland. “America encourages its political allies in Europe to promote this revival of spirit, and the growing influence of patriotic European parties indeed gives cause for great optimism,” reads one section of the document. European leaders have accused the Trump administration of creating ideological alliances with what are called “far-right” parties on the continent. The BBC reported that former Swedish Prime Minister Carl Bildt wrote that the document “places itself to the right of the extreme right.” Per a Deutsche Welle report, German chancellor Friedrich Merz said parts of the strategic document were “unacceptable to us from a European perspective.” Merz called for Europe to become strategically independent of the US.