The defence allocation numbers for the financial year 2024-25 may disappoint observers. India’s FY 2024-25 defence budget stands at a not inconsiderable ₹6.21 trillion (US $74.4 billion), which is a 4.7% nominal increase over last year. But here is what the numbers don’t bear out: after accounting for inflation, this represents a real-term contraction of roughly 6%, pushing defence spending to its lowest level as a share of GDP since the 1960s, reports the International Institute for Strategic Studies in its annual defence review, The Military Balance 2025.

This is seen not as a temporary shock, but as an entrenched policy direction and a result of fiscal inertia. India has redefined its fiscal framework by tying expenditure discipline to debt-to-GDP ratios, constraining discretionary spending in the critical defence sector even as the security environment deteriorates rapidly. Defence spending has fallen not only relative to GDP but also relative to total government expenditure, indicating an apparent gradual deprioritisation within the broader budgetary framework. The government is working to build economic strength, but experts believe that the relatively unimpressive (indeed falling) real rate of increase of the defence budget is frustrating key national security objectives.

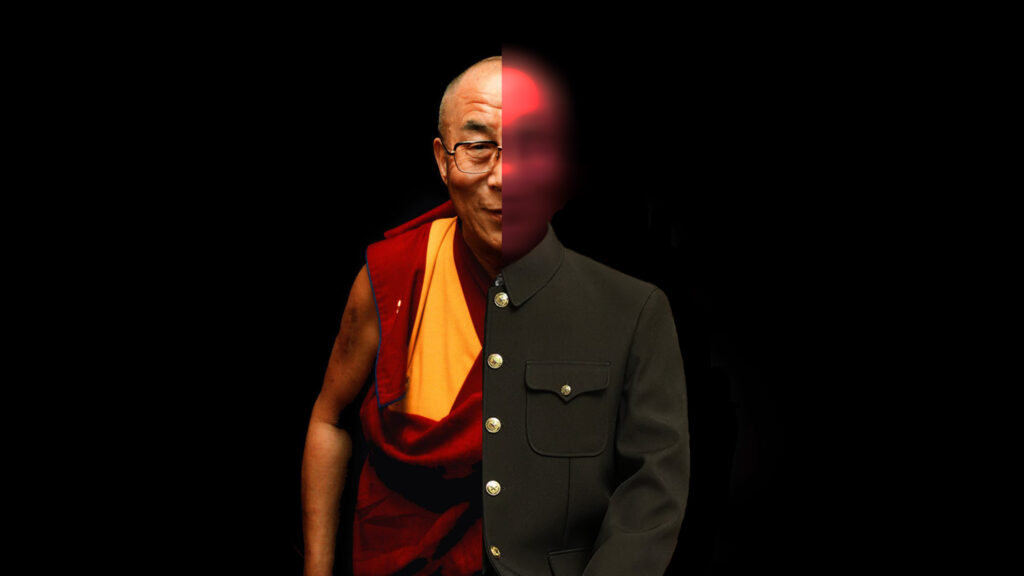

The contrasts remain stark. Across Asia, defence budgets—particularly among the US allies and China— continue growing in real terms. The Indian subcontinent, as a sub-region, recorded negative real-term growth, with India being the principal driver. At a moment when China expands defence spending at a faster real rate than one can imagine, and maintains decisive advantages in infrastructure, force modernisation, and high-end capabilities along the Himalayan frontier and the Indian Ocean, it may be time to ask what rationale, if any, exists behind India choosing fiscal discipline over strategic necessity.

The operational consequences are immediate. India maintains one of the world’s largest standing forces, and yet, as the Military Balance 2025 highlights, persistent weaknesses plague us: inadequate logistics, ammunition shortages, spare-part constraints, and insufficient maintenance personnel, among others. These deficiencies aren’t new, but inflation-adjusted budget cuts exacerbate them by squeezing the revenue and expenditure needed to sustain readiness. Modernisation programmes (already prone to delays and cost overruns) become particularly vulnerable. Capital outlays lose purchasing power first during inflation, slowing the induction of new platforms across land, air, and naval forces precisely when India attempts to shift from manpower-heavy forces to technology-intensive capabilities.

India has made progress toward joint theatre commands, scheduled for launch by mid-2025, more than a decade after China implemented similar reforms. But structural reforms require sustained investment: upfront spending on joint logistics, communications, training, and command infrastructure. Theatre integration without adequate financing becomes reorganisation without transformation.

China’s 2024-25 defense budget stands at $230=240 billion officially, $300+ billion with R&D, paramilitary forces, and off-budget items. India allocates $74–75 billion. China outspends India by over 3:1 officially, approaching 4:1–5:1 in effective terms (The Military Balance 2025). This isn’t a spending gap but a deterrence crisis.

This divergence has a clear trajectory: China grows in real purchasing power while India stagnates. China maintains 6-7% nominal increases exceeding inflation, funding continuous naval construction— the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) is now the world’s largest navy by hull count—missile forces, space systems, advanced ISR. India’s 4-5% nominal rises fall below defense-specific inflation. Revenue expenditure crowds out capital investment. India pays for the past instead of preparing for the future.

This divergence erodes India’s escalation capacity. China’s sustained investment enables rapid force regeneration and high-tempo operations. India’s capital constraints limit surge capacity and crisis endurance, giving China confidence that time favours it in LAC standoffs: a dangerous incentive in repeated crises. What is more destabilising is the fact that this is a divergence that keeps compounding, not a static gap. Each year widens the deterrence imbalance, increasing crisis frequency while reducing stability along the India-China frontier.

The Chinese Communist military is outmatched by the Indian armed forces in battlefield experience and operational readiness, a fact borne out in the manner in which the Indian Army achieved total victory over the numerically and technologically superior Chinese in the war of 1967. But if it is not fixed soon, the sheer spending gap will inevitably even out the Indian soldier’s prowess in favour of the inexperienced, tactically unimpressive but resource-rich Chinese.

The Indian government’s response has been to engage in intensified indigenisation under the “Make in India” scheme. Over 65% of the capital budget has been spent on domestic firms, with targets rising to 75%. This strengthens long-term industrial self-reliance and reduces exposure to external supply shocks. But progress remains slow, uneven, with limited foreign direct investment and technological depth. In the short term, indigenisation doesn’t offset declining real expenditure. Domestic systems face longer development timelines, and capability gaps persist even as exorbitantly expensive imports are permitted either as direct purchases or as Semi- or Completely-Knocked Down Kits (SKDs, CKDs) that are pre-made foreign packages to be assembled in India.

India remains the third-largest defence spender globally, but its share of global defence spending, being only 3%, reflects the growing asymmetry in defence geopolitics. Sustained underinvestment risks are locking India into a reactive posture: managing shortages, extending the service lives of legacy platforms, rather than enabling proactive force transformation. The real-value decline isn’t a short-term anomaly, but a structural stressor that constrains readiness, slows modernisation, and widens relative capability gaps at a moment of heightened Chinese aggression across Asia.

The question is not whether the government of India can afford robust defence spending (it can), it is whether it can afford not to.