On July 2, 2025, the 14th Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, confirmed his reincarnation. The Dalai Lama’s announcement reassured the Tibetan community across the world and in occupied Tibet. A statement released by the office of the Dalai Lama said that upon his death, he would be reincarnated and the 600-year-old institution of the Dalai Lama would continue with the 15th Dalai Lama, to be identified by elder Lamas of the Tibetan Buddhist order. The Dalai Lama specified that the Gaden Phodrang Trust “has sole authority to recognise his reincarnation in consultation with the heads of Tibetan Buddhist traditions”. He stressed that the search “should be carried out … in accordance with past tradition” and emphatically added, “no one else has any such authority to interfere in this matter.” This assertion was directed at the Chinese Communists, who have tried for decades to discredit and replace the institution of the Dalai Lama, the highest spiritual authority of Buddhists around Asia and the world. Within hours of the Dalai Lama’s statement, China’s Foreign Ministry responded that the Dalai Lama’s successor “must comply with Chinese laws and regulations as well as religious rituals and historical conventions,” spokesman Mao Ning told reporters. Wishing to legitimise its occupation of Tibet, China has maintained that any new Dalai Lama must be approved by Beijing, using the centuries-old golden urn method devised under Qing emperors. Officials claimed that the Dalai Lama’s reincarnation is an internal Chinese affair and insisted that “Tibetan Buddhism was born in China” and must follow the diktats of the Chinese Communist Party.

In 1995, the Dalai Lama recognised in similar fashion the reincarnation of the Panchem Lama, the second highest authority in Tibetan Buddhism after the Dalai Lama. Days after recognition was conferred on Gedhun Choekyi Nyima as the 11th Panchem Lama, the Chinese government kidnapped him and his family. They have not been heard from since. Soon afterward, the Chinese declared their own pretender to the title of Panchem Lama, Gyaincain Norbu, who has been propped up by the Chinese state ever since and has toed the Communist Party line.

Chinese media and officials now portray Norbu as a model patriot, and he was made vice-president of the state-controlled Buddhist association. In his public appearances, he is often quoted praising Communist Party politics in Tibet. In a June 2025 meeting with President Xi Jinping, Norbu explicitly pledged loyalty to the CCP and vowed to advance “the sinicisation of religion,” according to state media. He reportedly promised to “firmly support the leadership of the [Communist] Party” and to carry forward “the patriotic and religious traditions” of Tibetan Buddhism in service of a “strong sense of community for the Chinese nation.”

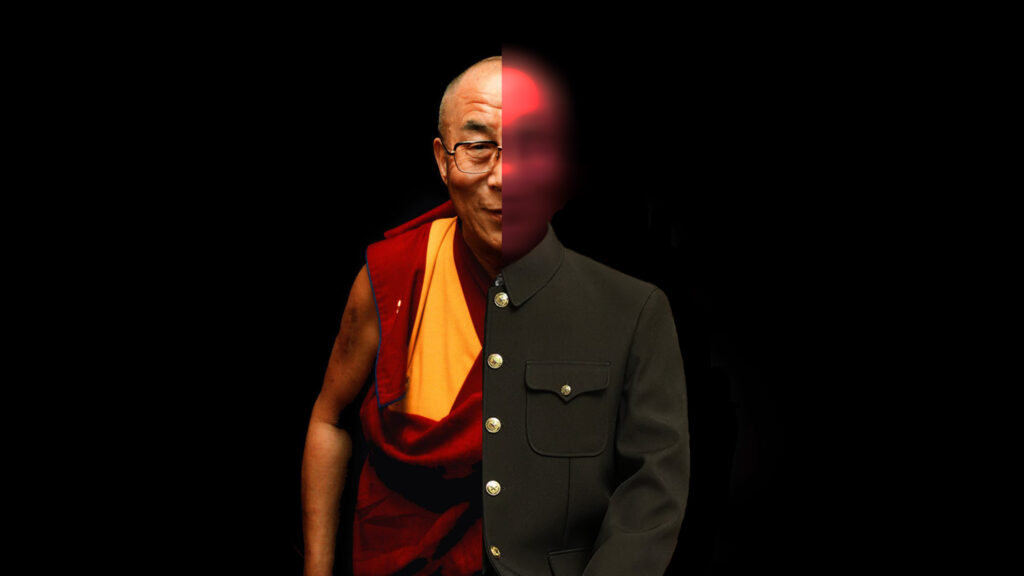

In this light, China’s insistence on controlling the Dalai Lama’s successor is widely seen by experts as politically motivated. By installing a puppet Panchen Lama, Beijing had created the pretext that will now allow it to install a Chinese Dalai Lama.

Observers have long anticipated the present conflict between the free Tibetans and the Chinese Communists, which could result in the Dalai Lama’s reincarnation being disputed by a Chinese puppet similar to Norbu. The only way to prevent this situation was for the Chinese state to pursue rapprochement with the Dalai Lama and the free Tibetan government in Dharamshala, the CAR (Central Tibetan Administration.) This has not happened, and with the Dalai Lama having confirmed the process of reincarnation, it is all but certain that the world will witness the creation of the “anti-Dalai Lama” inside China.

India is home to the Dalai Lama, the free Tibetan government and a large Tibetan community. Having supported the Tibetans’ right to self-determination and to their homeland over decades, the Indian government will have to decide if its policy will continue with the next Dalai Lama, something that would greatly discomfit China and impact Indo-Chinese relations. On July 4, Union Minister Kiren Rijiju publicly backed the Dalai Lama’s authority on succession, stating that “no one has the right to interfere or decide who the successor of the Dalai Lama will be” and that only the Dalai Lama and Tibetan Buddhist authorities have the right to make that decision. He also travelled to Dharamshala to attend the Dalai Lama’s 90th birthday on July 6, accompanied by Union minister Rajiv Ranjan Singh. The official support is a clear indication of the fact that New Delhi won’t accept Beijing’s claim over the succeeding Dalai Lama without a fair fight.

The Chinese foreign ministry, which does not recognise the Tibetans’ right to self-government, asked India to “stop using Tibet issues to interfere in China’s domestic affairs” in response to the minister’s message of support to the embattled nation. Chinese media, which is controlled by the state, abounds with threats against India about using what they call the “Northeast Card,” a reference to China’s support for armed secessionist movements in Indian states on the China border. Official Chinese commentary has hinted that Beijing could leverage ties with Pakistan and Bangladesh to fund armed insurrectionists inside India, noting for example the recent China–Pakistan–Bangladesh trilateral meeting in Kunming as a veiled signal.

To fully understand the depth of this crisis, one must unpack China’s version of Tibetan history. Beijing’s official history depicts Tibet as a backward “feudal serfdom” before 1950, and the Communist invasion as a form of liberation. The state media emphasized the Dalai Lama’s dual religious-political role as a prime example of the ‘feudal’ excess they claim to have ended. Yet ironically, the same Party that once decried theocracy, proclaims itself the sole guardian of Tibetan Buddhism today. Leading Chinese intellectuals, like Hu Shi and Chen Duxiu, once called Buddhism a ‘misfortune for China’ and ‘an obstacle to progress.’

Today, the Party itself insists that it can alone manage reincarnations and preserve Tibetan culture and religion, albeit on Chinese terms. This reversal—from denouncing Buddhism to tightly controlling it—punctuates the political ambitions behind China’s claims.

Beijing also touts Tibet as a showcase of socialist development, with official claims that the “TAR” (Tibet Autonomous Region) is a ‘different planet’ of modern infrastructure, capable even of exporting development models to neighboring countries. In reality, however, research and data paint a far different picture, because in nearly all metrics— per capita GDP, local revenues, income equality— Tibet lags far behind. The urban-rural income gap in China is the largest, and successive economists have labeled Tibet’s economy as a ‘dependency economy,’ endlessly requiring new state investment just to sustain itself.

China itself sees Tibet’s ‘primary contradiction’ as economic underdevelopment and a ‘secondary contradiction’ as ethnic/religious tensions. For India, this comes as a reminder: the Dalai Lama’s succession dispute cannot, and should not, be viewed in isolation from Beijing’s grand strategy.

However, Tibet’s importance to China doesn’t just end on a cultural or a political note— it is also highly strategic. As the “roof of the world,” the Tibetan plateau provides a natural Himalayan buffer against India. The 1962 Sino-Indian war was fought over these heights, and Beijing still officially disputes the McMahon Line, the border between the Indian Union and Tibet. Moreover, Tibet is the water tower of Asia: the headwaters of the Mekong, Brahmaputra, Indus, and other rivers lie in Tibetan territory. Chinese control of these sources (via dams and diversions) gives Beijing tremendous leverage over downstream neighbors. In 2021, for example, Chinese dam construction briefly cut off about 50% of the flow in the Mekong, causing outcry in Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, and Laos.

Tibet also sits atop vast mineral wealth— notably, lithium deposits, which are key to EV batteries. In the escalating Sino-American trade war, China is eager to secure its critical resources. By integrating Tibet into its economy, Beijing aims to reduce reliance on foreign suppliers. Beijing believes the appointment of its own anti-Dalai Lama would help “legitimize” Chinese rule over Tibet and eradicate opposition to mining and infrastructure projects.

The Chinese succession plan has already been decades in the making, Beijing will now attempt to confuse and undercut the real institution of the Dalai Lama. Possibly, a Chinese claimant will be forced on Tibet when the 14th Dalai Lama passes. While the next Dalai Lama will be found by traditional Tibetan lamas (likely outside territories under Chinese control, as the Dalai Lama has insisted “the successor will be born in the free world”), the anti-Dalai Lama will be proclaimed by Beijing. The attempted schism could bring significant ruin to the centuries-old ethos of Tibetan Buddhism. Meanwhile, China will continue pushing its narrative through its controlled Panchen Lama, and the ‘loyal’ Tibetan clergy, claiming historical legitimacy.

For India, this succession crisis comes with high stakes and one clear route. New Delhi has always hesitated to openly challenge China’s authority inside Tibet even as China supports Indian separatists and tries to interfere in India’s sovereign territory. The time may finally be at hand to hold Beijing to account and point out decades of Chinese erasure of Tibetan identity and nationhood. Many in Delhi consider it the Union government’s moral responsibility to keep backing the Dalai Lama now that he has forced Beijing’s hand by his announcement, compelling the Chinese state to bring out into the open its sustained campaign against the man who is regarded by many as the most popular spiritual leader in the world.

In the end, the Dalai Lama succession crisis reflects a larger truth: Tibet is at the crossroads of history. It is where Chinese imperial ambition, Himalayan geography, and the aspirations of an ancient people all converge. The moral authority of the Dalai Lama’s succession plan stands at odds with the legalistic, party-driven approach of Beijing, making this clash as much about values and history as it is about minerals and rivers.

Prime Minister Modi offered hope to Tibetans and sparked outrage in China on his very first day in office by inviting then-President (Sikyong) of the free Tibetan government in Dharamshala, Lobsang Sangay, to his inauguration. But Modi, like past Prime Ministers of India, has hesitated to strengthen support to the Tibetan cause and take a firm stand against China, whose ambitions extend beyond control of Tibet and well into the sovereign territories of India, Nepal and Bhutan. No better opportunity may present itself for the Prime Minister to display India’s resolve to defend the values of freedom and democracy to the world in the near future.